The Federation of Labour (FOL) was a central force in the history of New Zealand’s trade unions. It was established in 1937 and unified a fragmented labour movement. Its goal was simple, to give working people a powerful, central voice. Here, we look at the key milestones between the establishment of the FOL in 1937, and the formation of the Council of Trade Unions (CTU) in 1987.

1937: A Turning Point in Union History

Before 1937, the trade unions in New Zealand were divided, with the militant Alliance of Labour on one side and the moderate Trades and Labour Councils Federation on the other. The Great Depression had left unions struggling, but the election of the Labour Government in 1935 marked the beginning of a new era. The government’s policies, including compulsory unionism, led to a significant increase in union membership, setting the stage for the formation of the Federation of Labour.

The Road to Unity

Despite a public row between union leaders in early 1937, the pressure for a unified labour movement continued to grow. The controversy, played out in Wellington’s Evening Post, highlighted deep divisions but also underscored the need for a central organisation. After intense behind-the-scenes negotiations, a national industrial conference was convened in Wellington on April 14, 1937. Over 300 delegates, representing 90% of New Zealand’s union members, attended and founded the Federation of Labour. What affiliated unions paid per member per year was a large part of the discussion. A fee of 6 shillings (about $45 dollars in today’s money) was settled on.

The Role of the FOL in New Zealand’s Economy

The formation of the FOL was followed by the establishment of a centralised wage-fixing system, which dominated employment relations for decades. The FOL played a critical role in negotiating with governments and advocating for workers’ rights, contributing to the creation of an egalitarian wage structure that became a cornerstone of the Welfare State. The FOL became a key player in New Zealand’s national economy.

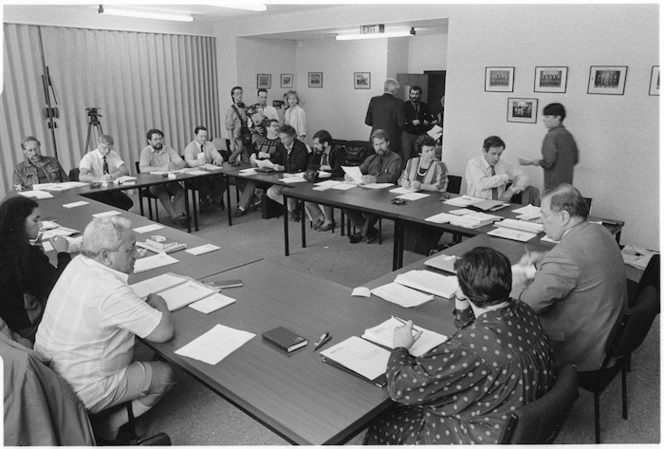

Back row (from left): W Watson (?), D Stalker, F Tercel, W F Campbell, A Black, R P Smith, J Harris (?), E Lindley, J Queenan, R H Shaw, W Clark, T Stanley

Front row (from left): J Thorpe, F P Walsh, F D Cornwell (secretary), A McLagan (president), R Eddy (vice-president), J Roberts, F Gould, A Wathey.

New Zealand Federation of Labour: Photographs of Union activities. Ref: PAColl-0980-1-01. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22823874

Challenges and Controversies

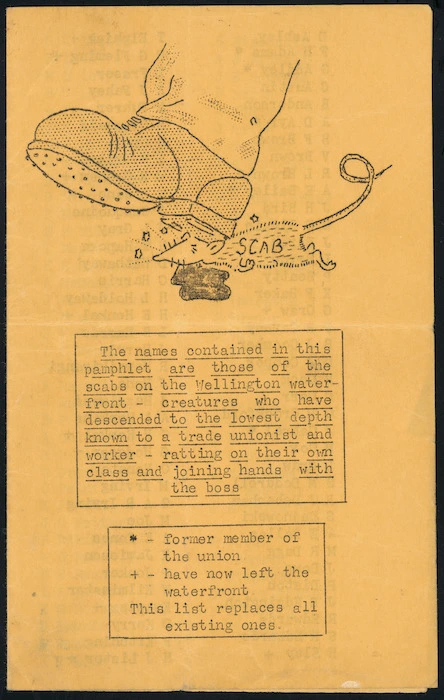

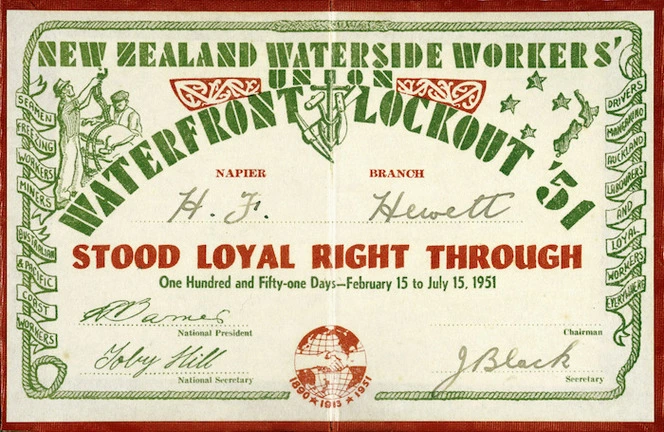

The post-World War II period brought significant challenges for the FOL. Militant unions, opposing the arbitration system, led to confrontations, most notably the 1951 Waterfront Lockout. The waterfront dispute lasted for 151 days, was the largest industrial conflict in our history, and saw up to 20,000 workers strike in solidarity with waterfront workers facing financial hardship and poor conditions.

Fig 4: [New Zealand Waterside Workers’ Union?] :Scab; the names contained in this pamphlet are those of the scabs on the Wellington waterfront – creatures who have descended to the lowest depth known to a trade unionist and worker – ratting on their own class and joining hands with the boss [1951]. Ref: Eph-A-LABOUR-1951-04-front. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22861384

The FOL played a key role in opposing the more hard-lined unions, ultimately leading to the deregistration of the Waterside Workers’ Union and the establishment of 26 local unions in its place. The FOL, staunchly anti-militant, took a hard line against these unions, a stance that was widely supported by the broader union movement at the time.

“What the FOL did was inexcusable but throughout this period its leaders had the support of the great majority of unions.”

Peter Franks, Communications & Research Officer, Council of Trade Unions (1994 to 1999).

The Decline of the FOL and the Rise of the CTU

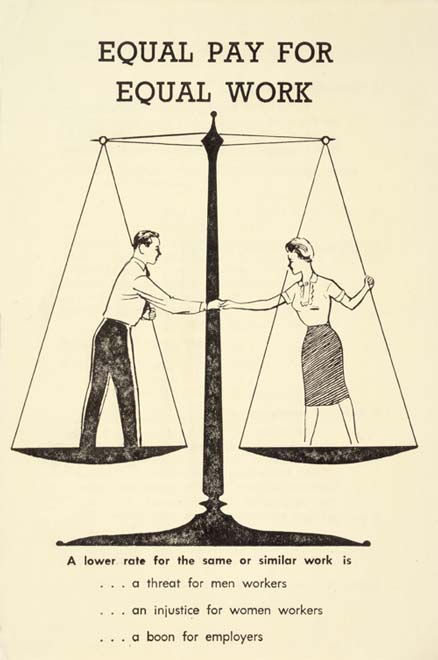

Fig 6: Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity. Council for Equal Pay and Opportunity: Equal pay for equal work. A lower rate for the same or similar work is … a threat for men workers … an injustice for women workers … a boon for employers. 1961.. [Ephemera of octavo size relating to women, women’s roles, activities, issues, in New Zealand]. Ref: Eph-A-WOMEN-1961-01. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22858323

By the late 1960s, the centralised wage-fixing system began to unravel, leading to economic instability and changing labour relations. The 1970s and 1980s were a see-saw of wage controls, industrial confrontations and compromises between the FOL, employers and governments against a backdrop of growing economic instability with rising inflation and unemployment.

The FOL started to rid itself of some of its conservatism, promoting a shift towards a more inclusive and diverse union movement. Debates on issues like equal pay, the Vietnam War, and apartheid gained prominence, and the demand for better representation of women and Māori grew.

Front row (from left): G H Andersen, Sonja Davies (Vice-president), W J Knox (President), K G Douglas (secretary), S P Jennings.

Ref: PAColl-9354-5-203. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/23129264

“Instability in the economy and employment relations helped push the private and state sector unions closer together.”

Peter Franks, Communications & Research Officer, Council of Trade Unions (1994 to 1999).

The need for a new approach became evident. In 1982, the PSA proposed a new, central union organisation, and after five years of debate, the Council of Trade Unions (CTU) was formed in 1987, pushing the FOL and the Combined State Unions out of existence. This marked the beginning of a new chapter in New Zealand’s labour history.

The Legacy of the FOL

The Federation of Labour’s history underscores the importance of having a national voice for workers. While the FOL was a product of its time, it laid the groundwork for the CTU, ensuring that the collective interests of all workers continue to be represented. The NZCTU Te Kauae Kaimahi continues the ongoing struggle for workers’ rights and the pursuit of social justice by responding to the ever-changing nature of issues that impact working people in Aotearoa New Zealand.

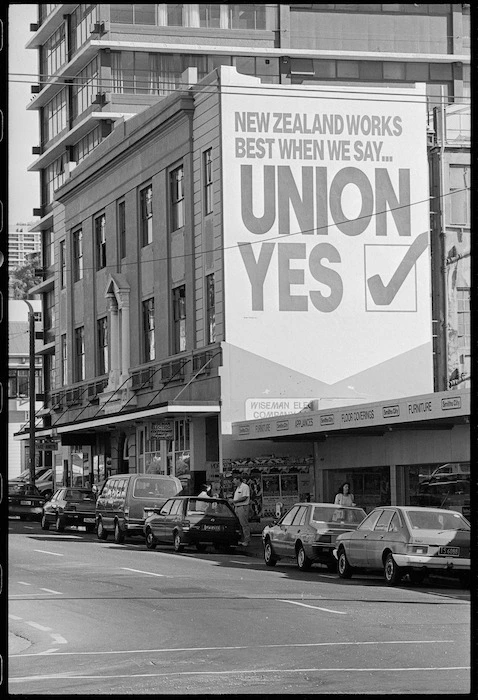

Fig 10: Wellington Trades Hall with union wall sign (1991). Dominion Post (Newspaper): Photographic negatives and prints of the Evening Post and Dominion newspapers. Ref: EP/1991/0861/16A-F. Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand. /records/22764467