Major structural changes to the economy have left workers out of pocket and changes are needed to address the imbalance, the Council of Trade Union (CTU) says following the release of a new Productivity Commission report.

“Labour share of income – the proportion of the total income of a country that goes to working people as distinct from the owners of capital – has been dropping for decades as a direct result of government decisions,” CTU Economist Bill Rosenberg says.

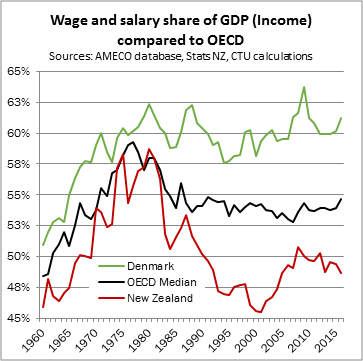

“The facts are clear. If wage and salary earners received the same share of the income generated in 2017 as they did in 1981 they would on average have been $11,500 better off. Their share of the total income generated dropped over that period from 58.7 percent to 48.7 percent. This means their annual incomes, plus other benefits such as employer superannuation contributions, would on average have been 21 percent higher in 2017 if their share had kept pace.”

“In the smaller sector of the economy that the Productivity Commission looked at workers, including self-employed people, would on average have been $8,400 better off in 2016*. Their share of the total income generated dropped over that period from 65.0 percent to 55.5 percent. This means their annual incomes, plus other benefits such as employer superannuation contributions, would on average have been 17 percent higher in 2016 if it had kept pace. ”

“If you look at the figures just over the previous cycle of Government, we see a similar pattern. If wage and salary earners were receiving the same share of the income as they were in 2009, their annual incomes plus other benefits would on average have been $2,500, or 4 percent higher in 2017. Workers in the sector the Commission looked at would on average have had $2,400 more or 5 percent higher annual incomes.”

“The falling labour income share shows that real wages have not been keeping up with income growth.”

“The Productivity Commission has failed to acknowledge the significant part played in this fall in workers’ share of the nation’s income by poor employment law and working people’s loss of bargaining power. They put greatest emphasis on technological change without providing evidence.”

“The largest falls can be identified with wage freezes in the early 1980s, commercialisation and privatisation which boosted profits while cutting wages in the late 1980s, and the Employment Contracts Act (ECA) in the 1990s. The effect of the ECA on labour share of income lasted until employment law changes in 2004 allowed a little of the share to be regained. The positive changes were put into reverse by the 2008-2017 National Government, which led to another steep fall starting in 2009.”

“Technology may have played some role, along with companies making excess profits due to lack of competition, as some research suggests overseas. But we need to look at the evidence in New Zealand and it is hard to dismiss the impact of government policies over a long period since the early 1980s.”

“The Productivity Commission asserts that “New Zealand has not experienced the significant falls in the labour income share seen in other countries over the last two decades.” That ignores the longer run of evidence and the effect of the changes in employment law. New Zealand still has one of the lowest wage and salary shares of the country’s income in the OECD,” Bill Rosenberg says.

Ends

* Note 2016 figures latest available.

The Productivity Commission’s report is available: www.productivity.govt.nz/sites/default/files/The%20Labour%20Income%20Share%20in%20New%20Zealand%20March%202018.pdf

For graphs on the labour share of income produced by Dr Rosenberg for free use, see: